The nation’s fastest-sinking city is Houston, with more than 40% of its area dropping more than 5 millimeters (about 1/5 inch) per year, and 12% sinking at twice that rate.

kagis

https://texaslivingwaters.org/groundwater/subsidence-houston-galveston-region/

Understanding subsidence in the Houston-Galveston region

Since 1836, groundwater withdrawals have caused about 3,200 square miles of the Houston-Galveston area to subside (or sink) more than a foot, with some areas subsiding as much as 12 to 13 feet.

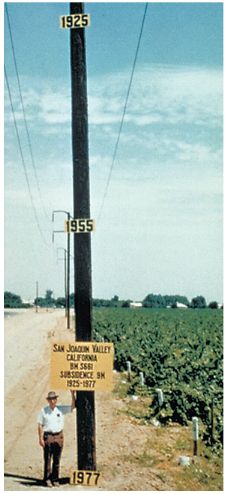

Noob-tier numbers, Texas. Here’s a photo from 1977 in California showing land subsidence on a telephone pole from 1925 to 1977.

https://water.usgs.gov/ogw/pubs/fs00165/Images/fig2.jpg

The pole is just an ordinary pole. In 1977, after measuring land subsidence over time, they put the signs up on it to illustrate how far the land had sunk. They could have put the signs on anything tall enough to provide enough space.